Ishizuka Sensei Has Passed Away... A Master Leaves Us

The presence, actions, words, and gaze of a master or a person can change a life... In the practice of any discipline, be it martial, artistic, etc., the master-disciple relationship remains the central pillar of knowledge transmission. This relationship manifests at every stage of transmission, from life to death, and even after.

While the master is alive, the disciple is both the vessel for the master's transmission and a reflection of the master in technique and knowledge, but must also have that extra something in the heart, which allows the master not only to recognize himself in the disciple but also to show human qualities and deep benevolence in patience, which gives the necessary impetus for the continuity of knowledge.

After the master's death, the disciple becomes his living memory and fully manifests the transmission while forming the bridge between the transmission of the past and the reality of the current era. The disciple must learn to fill the void left by the master's absence and give meaning to this emptiness... It is in this particular context, following the death of the master, that I would like to talk to you about Ishizuka sensei, whom I respectfully called Shishō (師匠), "Master." I met him during my first trip to Japan in the summer of the year 1989-1990, I was just 17, he was 40.

Who is Ishizuka sensei?

Born in February 1948 in Noda, Chiba Prefecture, the city where his master, Hatsumi Masaaki, was also born—the sole successor of Takamatsu Toshitsugu, head of 9 Ryū-ha, director of the Bujinkan organization. Within the Bujinkan, his name is deeply divisive. In all discussions, his name is met with respect and fear, jealousy and envy, misunderstanding and hidden admiration... Why was and does his name remain so polarizing?

Undoubtedly, it is because he maintained intact the "Link" with the art of the 9 Ryū-ha of Takamatsu sensei, as well as a deep and rigorous practice of all the technical details and psychological aspects of Ninjutsu, thanks to his unique master-disciple relationship with Hatsumi sensei.

I heard several times from Hatsumi sensei: « かセム、俺の事の一番詳しいは哲ちゃんだ »,"Kacem, Techan is the one who knows everything about me!" or « 一番修行したのは哲ちゃんだよ»,"The one who has practiced and studied the most deeply is Techan," etc. He was the only one for whom Hatsumi sensei used the term Chan (ちゃん) and called by his first name, which already showed the deep relationship, like a father with his son. Regarding their unique relationship, I had the chance to hear directly from the late Oguri and Seno Shihan, first-generation disciples who, like Ishizuka sensei, had the immense privilege of meeting Takamatsu sensei a year before his death.

The same sentiment was shared among other Japanese shihan of the organization, old and young, even those who received the "sōke" diploma, critics or not, everyone in the Bujinkan had seen and heard about the deep relationship between Hatsumi sensei and Ishizuka sensei, as well as his abilities and knowledge in the 9 Ryū-ha. In the practice of combat techniques, regardless of discipline or style, it is abilities and knowledge that command unanimous respect. In Ishizuka sensei's case, these allowed him to become the living memory of the initiatory history and knowledge of Hatsumi sensei.

The Encounter and Practice of a Strange Art: Ninjutsu

It was in 1963, at the age of 16, that Ishizuka sensei met Hatsumi sensei. The latter was 32 and had just started his initiation under Takamatsu sensei six years prior. Like many Japanese at that time, Ishizuka sensei practiced Jūdō in his high school club. With the approach of the Tokyo Olympics (October 1964), the first in Asia, where Jūdō was presented for the first time as an Olympic discipline, there was excitement around Jūdō with TV shows, articles, books, etc.

Very diligent in Jūdō, he also attended other high school clubs where Shorinji-Kenpō and Aikidō were taught. However, he found Jūdō more physical, especially enjoying randori. He had heard of Jūjutsu, but as he often said: "I was like all young Japanese of my age who only knew modern budō and were not at all interested in old and outdated arts like Jūjutsu. Moreover, it was very hard to find a master..."

During an inter-high school competition, he was injured in a match, dislocating his shoulder, and had to go to the osteopathy clinic in his town for treatment. The director and chief physician of the clinic was Hatsumi sensei, who would become his master.

Ishizuka sensei remembered his first time well: "Hatsumi sensei was 32, a 5th dan in Jūdō. He was quite strong for a Japanese. His care was highly sought after, always smiling and kind, the waiting room was always packed. From 1960 to 1965, there was a ninja boom in Japan—anime, manga, novels, films, etc.—and Hatsumi sensei was often asked to present the history and techniques of ninjutsu on TV, such as the show Ninja sen Ichi-ya or as a historical consultant and choreographer for fight scenes in the film Shinobi no mono with actor Ishikawa Raizō (1931-1969). In his clinic's waiting room, there were many photos taken during various TV shows, on set, etc., and all the patients were in awe, myself included!"

While Hatsumi sensei treated his shoulder, he asked: "Ishizuka-kun, would you be interested in practicing ninjutsu?" "Ninjutsu? For me, who practiced Jūdō, the terms and disciplines of Jūjutsu or Ninjutsu were completely unknown. Since I lived in the same city as Hatsumi sensei, I often saw him, and each time he would ask: 'When will you come to practice?' Ishizuka sensei replied: 'For now, I am preparing for my university entrance exams. Once I finish...' After passing his exams and being accepted to the law faculty at Kokushi-kan University, he attended Hatsumi sensei's class for the first time at age 17. 'To this day, I haven't forgotten that first class; it's etched in me for life.'"

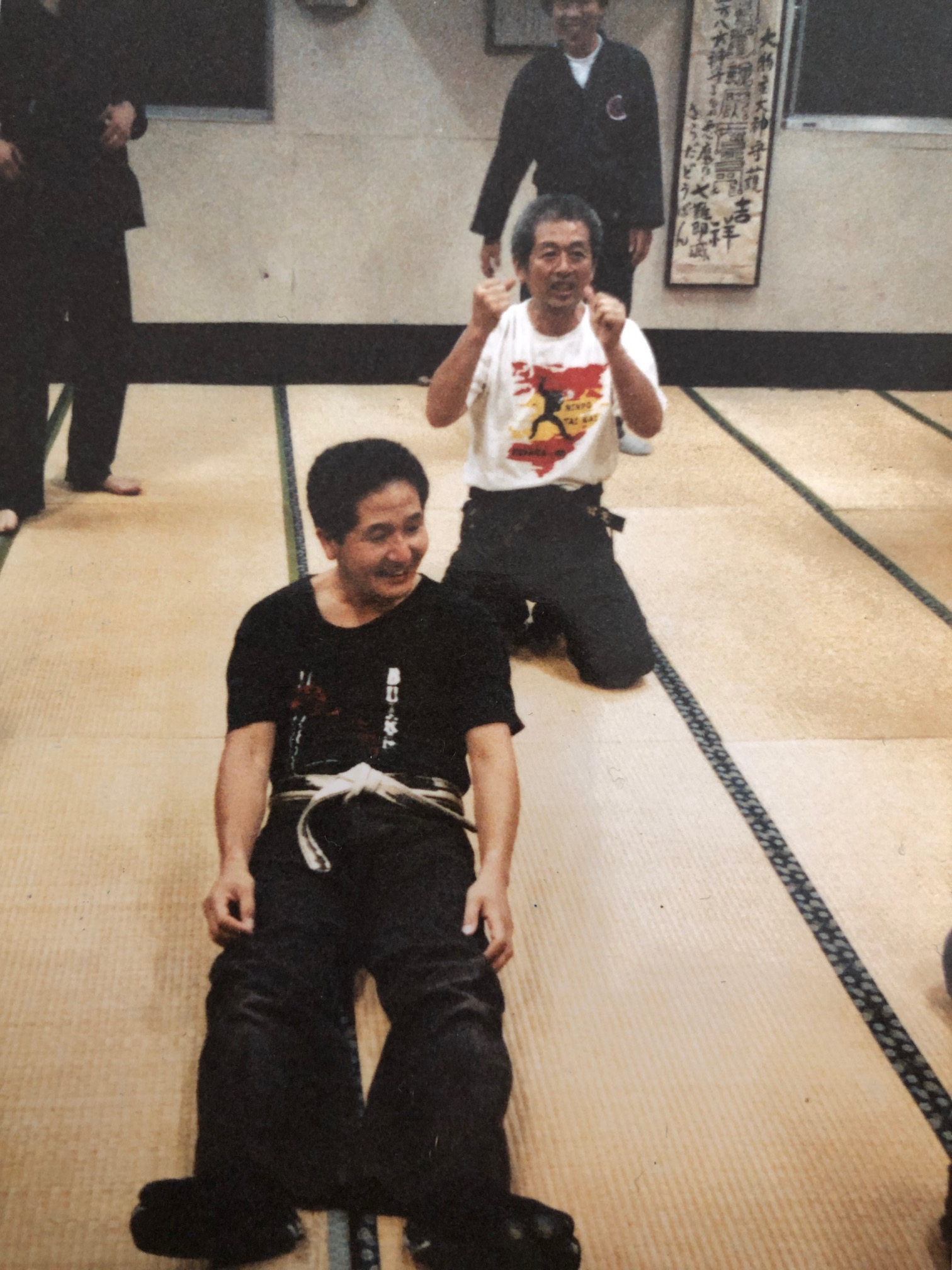

Ishizuka sensei recounted that for his first class, he wore his Jūdō black belt, confident in his abilities, but the class was a whole new story: "Immobilizations and chokes were pushed to the extreme, and sensei didn't stop even when I tapped out, attacks and pressure on vital points controlled at an unseen level, use of weapons and all kinds of objects, throws without the possibility of ukemi, etc. And when someone said, 'It hurts!' he would laugh: 'Oh, it hurts? I see... But you know, pain is proof your body is alive!' For young Ishizuka, it was a revelation, an unknown world of combat being transmitted just 5 minutes by bike from his home! He thought to himself: 'These techniques are incredibly painful... is this Ninjutsu?' That day, the proud young man received a lesson in humility, and at the next class, he was present, but this time with a white belt.

Disciple at Hatsumi Sensei's Dōjō

Very quickly, Ishizuka sensei became close to Hatsumi sensei and his family. He explained he had never seen someone as devoted to the practice of bujutsu as Hatsumi sensei. Despite his work as a chiropractor, Hatsumi sensei was constantly absorbed in practice, rain or shine, summer or winter, practicing, studying, copying the densho written by his master Takamatsu, whom he visited every weekend until his death. Each time he returned, he would teach us new things, correcting his own mistakes, constantly evolving...

Hatsumi sensei was well known in the world of Koryū; many masters visited him to study ancient techniques and forgotten Ryū-ha, especially ninjutsu. There were also foreigners in Japan seeking true Budō. It was a very different time from today; foreigners coming to Noda were rare. Some had become experts in various Budō disciplines, physically much stronger than Japanese. But this posed no difficulty for Hatsumi sensei, who accepted challenges and demonstrated techniques of the Ryū-ha he inherited, the use of Ninjutsu, etc. Ishizuka sensei met several times the famous Donn F. Draeger, who often visited Hatsumi sensei, as well as other masters like Nawa sensei. He also had the chance to attend demonstrations by the famous and controversial Fujita Seiko of the Kōga-ryū, etc.

Ishizuka sensei was tall for a Japanese, 170 cm, very athletic, yet he did not understand the combat techniques taught by Hatsumi sensei. He said: "I came from Jūdō, also had basics in Aikidō and Shorinji-Kenpō, so I used my hips, physical strength, etc. But with Hatsumi sensei, the movements and positions were another world. He taught several disciplines linked by a unique use of the body. He sometimes called it Kosshi-jutsu (骨指術), Koppōjutsu (骨法術), Taijutsu (體術). The hardest part was the positions, angular movements, constantly maintaining the line, hiding intention in all techniques, masking weight transfer, striking as if holding a weapon, and especially not using the hips. He often shouted, 'Forget Jūdō and the other disciplines, they pollute you!' He himself knew Jūdō and other Budō disciplines very well, being ranked in all, but after meeting Takamatsu sensei, he abandoned everything to devote himself solely to Takamatsu’s transmission..."

His dōjō was actually a room in his house; some furniture had to be moved, 8 tatami, so very small for 7 people. There was a makiwara in a corner, but very different from those used in Karate schools. One had to condition the hands, fingertips, knuckles, and toes.

Often during a throw, the floor would give way, so the tatami had to be removed to replace or fix the floorboards, interrupting the class and everyone would go home. As soon as I got home, the phone would ring and it was Hatsumi sensei: "Techan, come back, it's not finished." I would ask, "Should I call the others?" He replied, "No need. They live too far, come back, I'm waiting for you!" This happened more than once, to my mother's dismay!

Weapons practice was even more complex, as for long weapons like swords or sticks, it was nothing like what you usually saw. He used information from densho written by Takamatsu to have weapons made, as it was extremely difficult to find them in good condition, and I would go pick up the orders when ready. There was always something to study, a world to explore, with Hatsumi sensei it was always brimming with knowledge and practice…

A Deep Relationship

Little by little, Ishizuka sensei became sensei's right-hand man, and for good reason: his abilities and human qualities opened the doors to Hatsumi sensei's heart. A few notable facts: having no children, Hatsumi sensei and his late wife had wanted to adopt Ishizuka sensei, who spent more time at the Hatsumi’s than at his own home. However, Ishizuka sensei’s father did not agree, wanting his son to continue his law studies. For the choice of wife, again, it was the Hatsumi family who introduced Masako, who would become Ishizuka sensei’s wife and his unwavering support until the end of his life.

Three children were born from this union: the eldest named Mae, the second Sae, the youngest Aki. Combining the three names forms Masaaki, which is Hatsumi’s first name... About this, Ishizuka sensei said: "You know, I only realized this when Hatsumi sensei himself, who was ever-present in my life (at the birth of the children, marriage, deaths of parents, mutual friends, etc.) pointed out the name. Mako (his wife) and my parents were as surprised as I was! Personally, despite my deep respect for my master, naming my children after him is not my thing! I don’t have that blind student syndrome!"

Ishizuka sensei often emphasized that Hatsumi sensei was very attached to the notions of Bunbu-ryōdō (武文両道), Kyōyō (教養), and Butoku (武徳), inherited from Takamatsu sensei. His desire was to train young practitioners who would become assets to Japanese society, holding social positions to help and educate, setting an example through bujutsu practice, study, self-cultivation, and virtue. Even at 94, he urged students to always study and practice all forms of knowledge and disciplines, offering to others what he had always demanded of himself since meeting Takamatsu sensei. Studying music, painting, and calligraphy was an integral part of practicing the 9 Ryū-ha and bujutsu in general, to approach the ideal embodied by Takamatsu sensei.

Another bond that further deepened the connection between Hatsumi sensei and Ishizuka sensei was music, especially Hawaiian music, very popular among Hatsumi sensei’s generation. Alongside the practice of the 9 Ryū-ha, his studies, and then his work, Ishizuka sensei began studying Hawaiian music early and entered the music world as a guitarist and vocalist in a band, eventually performing professionally. Whenever Hatsumi sensei had the chance to sing and Ishizuka sensei was present, it was Ishizuka sensei he asked to accompany him.

His presence of mind and natural charisma naturally put him forward for all technical demonstrations on TV or other events, and for meetings with various masters who visited Hatsumi sensei. Being the only one among the first disciples (seven in number) who spoke English and Chinese, he handled correspondence with the first foreigners and was also editor-in-chief of the dōjō’s monthly newsletter, Ninyu (忍友). Thus, very few in the Bujinkan know, but he was the first appointed director of the small organization named Bujinkan, in honor of Takamatsu sensei, by Hatsumi sensei.

Loving combat, always ready to help and defend the weak, he was always chosen first by Hatsumi sensei to face practitioners of various disciplines who came to challenge Hatsumi sensei in his dōjō. His reputation in Noda and even at Kokushi-kan University was well established. With age, Ishizuka sensei became the gateway for all foreigners who came to study with Hatsumi sensei from the 1980s to the mid-1990s.

He was the first to travel abroad, to Sweden, on his honeymoon in 1975 after a brief stop in Paris... There he taught for the first time. From the mid-1980s, with US film productions by the Cannon group featuring Sho Kosugi, Dudikof, etc., the ninja and ninjutsu became "the" discipline of the moment, just as kung fu wushu had been, leading to renewed interest from foreigners, and so Hatsumi sensei was invited to give seminars abroad. After each trip, the person he called to discuss and share his thoughts and experiences was Ishizuka sensei...

His direct and sharp character, like his technique, his refusal of ranks, his perseverance and faith in what Hatsumi sensei transmitted to him, were not always well accepted, especially with his refusal to participate in the indiscriminate promotion and awarding of ranks. For Ishizuka sensei, who was assigned by Hatsumi sensei to teach the basics, the importance of martial rectitude, uprightness, and respect for the transmission of techniques was essential. A high vision of practice and its transmission could not go hand in hand with too free a promotion of ranks without knowing the student's intentions. As it takes time to know and polish knowledge, it takes time to know the student. Sometimes a higher rank revealed the student's true intentions...

Add to this the demands of his ever-evolving social position—he would become director of the crisis management office for Chiba Prefecture, overseeing fire stations, mobile first aid units, equipment and training, crucial in a country like Japan facing extreme weather. This involved heavy budgets, many meetings with mayors and governors, training managers, negotiations, leadership, etc.—an important position for which he was repeatedly honored for service to the nation, receiving in April 2015 the ultimate award from the Emperor of Japan.

However, always present, his obligations became heavier, family life, music, classes, etc., no longer allowed him to visit Hatsumi sensei whenever he called in the middle of the night to talk. This led to some distance from the Bujinkan organization. Nevertheless, despite a very busy schedule, Ishizuka sensei continued to teach a small number of students, which was no problem for him, as teaching was not for economic purposes but for the love of the art, keeping in mind the principle of martial transmission: Isshi sōden, a transmission to a single disciple. A transmission aiming for quality rather than quantity, so one good and true disciple is worth much more than a hundred who lack the qualities required to receive the transmission.

As Hatsumi sensei often taught him: "If you teach for money, sooner or later, you will lose your abilities and be controlled by the desire for gain, the practice of the art will disappear," which Takamatsu sensei had repeated to him many times. For Ishizuka sensei, there was no question of making money from teaching to support his family. For him, only the Sōke had the right to live from it, even if Hatsumi sensei continued his work until age 55, unable to keep up with the growing demand for seminars and patients, selling his clinic to devote himself exclusively to teaching... Ishizuka sensei explained that Hatsumi sensei always said Takamatsu sensei repeated several times that it was important to have a job and various qualifications, fields of interest, to broaden one's studies so as not to become closed-minded and rigid from Budō practice or a slave to teaching to the point of selling knowledge, which led to the corruption of Koryū with the multiplication of dōjō and compartmentalization of disciplines during the Edo period.

Of course, there was nothing wrong with receiving financial compensation for teaching, but one had to be deeply aware of the priorities related to practice and study, the well-being (physical and mental), and the future of the disciple. Until his death last March, Ishizuka sensei remained faithful to this thought... I witnessed it many times.

Very early on, Ishizuka sensei had fulfilled Hatsumi sensei's wish for his disciples to excel professionally, in family, and martially. In this respect, of all Hatsumi sensei's disciples, Ishizuka sensei was far ahead, always recognized and respected by all, despite difficulties and jealousy.

The Meeting with Takamatsu Sensei

Ishizuka sensei had heard many stories about Takamatsu sensei. After each class, or alone with Hatsumi sensei, there was always an anecdote, a saying, a fact about Takamatsu sensei, his hands, his technique, his words, reported by Hatsumi sensei. For example, every letter sent by Takamatsu sensei was sometimes read in front of Ishizuka sensei when he visited.

Ishizuka sensei often said: "You know, when I visited sensei at home, he was always busy copying Takamatsu sensei's densho. I would say, 'Sensei, why not photocopy them, it would be simpler and faster, right?' To which Hatsumi sensei replied: 'You see, Takamatsu sensei took the time to write his knowledge, the transmission is to copy all aspects of the master, so copying his writing allows me to get closer to him and deepen what he transmitted to me... even if I see him every weekend!'"

"Each time Hatsumi sensei returned from Takamatsu, there was always something to review, correct, rectify, study. I had never seen such devotion, admiration, and respect for a master," said Ishizuka sensei.

The day came when Hatsumi sensei decided to take his group of seven disciples to meet Takamatsu sensei, in 1970, two years before Takamatsu sensei's death, he was 80. For the small group, it was quite a journey: unable to afford the direct Shinkansen train, it was agreed among the disciples to go by train to Nagoya and rent a car to go to Nara, Kashiwara city, where Takamatsu sensei lived. Arriving in Nagoya, the only one who hadn't forgotten his driver's license and had the money for the car was who? Ishizuka sensei, which says a lot about the character of each disciple, which would become clearer much later in their choices and life paths.

I heard the story of the meeting several times from Ishizuka sensei, to translate for many students who visited his dōjō and attended his classes. I also questioned the disciples present, like the late Oguri, Seno, or the robust Kobayashi, who told me that all had forgotten their licenses and didn't have the necessary money. Kobayashi added: "Techan was special, and that's why Hatsumi sensei always called on him, for everything."

Here is how Ishizuka sensei recounted this meeting: "Arriving at Takamatsu sensei's house, his wife guided us to the second floor, to the guest room. I was sitting in front of Hatsumi sensei, in seiza, with my back to the sliding door. It was a very old house; it was easy to hear footsteps on the floor. And Hatsumi sensei said: 'Sensei is coming.' How?! I hadn't even heard footsteps on the narrow wooden stairs, nor the sliding door moving! And Takamatsu appeared before us, I turned my head to see him, he had long white hair falling over his shoulders, one eye taken by illness, he was nothing like the person in the photo I was used to. At the sight of him, something cold emanated from him that gave me goosebumps and made me quickly move aside to make room. He sat in front of us, you would never have guessed he was in his 80s, He said, 'Welcome. Thank you sincerely for making such a long journey. Please, make yourselves comfortable.' Impossible…even meeting his gaze was out of the question.

Much later, I told Sensei that seeing him gave me goosebumps, that there was a coldness about him, and that when he approached to sit down, he seemed to glide across the tatami. Hatsumi Sensei smiled and replied, “No, he’s actually very kind and benevolent. But what you probably sensed is something only people who have survived life-and-death situations—like Takamatsu—carry with them. It’s a bit like the feeling you get from someone who has had to kill to survive.

His hands were incredible! The practice he imposed on himself had completely transformed them. But he said: "Avoid doing as I did, it's not practical. Especially in front of women!" Yet you could see his fingers and hands were light, supple, just by the way he handled the tea utensils to serve us. Then we walked to the Kashiwara Shrine for a class. The way he walked—gliding effortlessly, without any unnecessary movement—his presence both distant and close, somehow present yet absent, as if he saw everything… It was all so strange, so unlike anything normal or human. Incredible! That's what I remembered most. It was another world.

Then seeing Hatsumi sensei receive techniques and fall like a feather was truly surprising! Takamatsu sensei demonstrated sword techniques—you would never have guessed he was in his 80s! Honestly, I understood nothing. There was something unfathomable about him, his movements when he did techniques on sensei were hard to understand... everything was direct, simple, without unnecessary movement, and you could see he touched little but the result on Hatsumi sensei was incredible.

Years later, when I reached 70, recalling this meeting during a discussion with Hatsumi sensei, I could say with experience that Takamatsu sensei's movements were the expression of Mutō-dori, nothing unnecessary, a "wind of combat," a river, an ocean in motion."

A few days after this meeting, Hatsumi sensei showed us an 8mm film of Takamatsu sensei at 60, demonstrating combat techniques of the 9 Ryū-ha, kenjutsu, bojutsu, yari, naginata, jōjutsu, hanbō, kusarigama, etc. That's when I realized I had to change my way of practicing to get closer to this art, and since then I have never stopped practicing in this direction."

Ishizuka Sensei's Dōjō

"At my place, no ranks! Just practice and study with respect. If you're looking for quick ranks or to do techniques without meaning, go to other dōjō (of the Bujinkan)!" That's what Ishizuka sensei often said. Or, "We don't joke with Budō practice! It's serious! I'm not a Budō salesman, I don't teach what others do. Hatsumi sensei didn't transmit his knowledge to me to manipulate or confuse students." During classes, when students got injured or someone wanted to show off their strength, resulting in injury, Ishizuka sensei always reminded: "Don't confuse violence with effectiveness. Budō, Bujutsu, is not about deploying violence or showing off to others! Injuring a student or peer in class simply shows you don't master the art, it's proof of immaturity and ignorance. The art goes beyond violence. You must be careful not to injure to avoid creating resentment and giving a bad image of the art."

At every class with foreign students, as with Japanese, he repeated: "You come from far to practice, you make sacrifices to come to Japan, you must be serious and honest in practice, especially when you are an instructor!" "You have a black belt, you're 10th dan or 15th dan and you can't even do the basic techniques? And you want to study the advanced techniques of the schools?! You don't realize that against a judoka, karateka, or boxer, it's over with the first blow!" "If you can't do this technique, it's because you didn't receive the correct teaching, so it's not your fault but your instructor's, who is incompetent. I will give you the necessary corrections, and it's up to you to practice deeply to master the technique. However, if after I've taught you, you choose to remain ignorant, the fault is yours, not your instructor's!"

No more than three techniques were taught per class, never any personal development or useless techniques without martial, technical, or pedagogical foundation. Such was Ishizuka sensei's teaching. He taught as he had learned directly from his master, Hatsumi sensei.

The Responsibility of the Sōke Title, His Book, the Last Days...

Ishizuka sensei did not chase after ranks. When, to keep him close, Hatsumi sensei offered him the Menkyō kaiden of Kukishin-ryū, one of the 9 Ryū-ha, because a Jūdō teacher had offered Ishizuka sensei a 3rd dan and a place as assistant in his class, Ishizuka sensei said: "I didn't even know what a menkyō kaiden was, it meant nothing to me. I was more interested in a 3rd dan in Jūdō! Moreover, I knew nothing about Kukishin-ryū, so I couldn't accept a diploma whose history or importance in Koryū transmission I didn't know. Hatsumi sensei convinced me by saying: 'Takamatsu sensei gave me the Sōke titles when I wasn't at the level, and I practiced and studied relentlessly! That motivated me to always practice more so he would be proud of me and not ashamed! You can do the same, right?! And Kukishin-ryū suits you well, there are many combat techniques, strikes, throws, locks, weapons, you'll see if you practice...' And that's how I accepted the menkyō kaiden, of course I told no one! I practiced, and the more I advanced, the more humility grew in me before the knowledge and wisdom of this Ryū. Hatsumi sensei always gave the grade before you reached the required level. It wasn't common in our time, especially compared to grades in other modern styles. But as you know, that was the custom in the past; once the successor was chosen, the master gave him all the knowledge, so that it would push him to survive and practice. Hatsumi sensei did as Takamatsu sensei did. He thought, like him, the student would go deeply into practice. In any case, that was my case!"

Thus, Ishizuka sensei was one of the first to receive menkyō kaiden in the 9 Ryū-ha but also to copy the densho with a brush. With his legal studies background, Ishizuka sensei early on kept a journal of his practice with Hatsumi sensei. He had many notebooks where combat techniques and their variations, explanations, oral teachings of Hatsumi sensei were written. He kept this writing discipline until he became blind a year before he died, in March 2025.

58 years after being accepted as a disciple by Hatsumi sensei, history repeated itself on October 10, 2019, when Hatsumi sensei called him to give him the title of Sōke of Gyokko-ryū kosshijutsu, the main Ryū-ha that forms the "Link" with the other eight. Again, he was the first to receive it. A year later, on March 13, he received two suitcases of 50 kg each containing all the transmission documents, densho and makimono, of the 9 Ryū-ha, as well as various studies written by Takamatsu sensei. To this day, no one else has received these documents. Why? Only Hatsumi sensei knows.

During the Covid period, Ishizuka sensei, alone in his dōjō, began copying the densho, discovering for the first time in his life the densho written by Takamatsu sensei, because, as he sincerely admitted several times, "You know, we had never seen the originals written by Takamatsu sensei. Hatsumi sensei never showed us the originals, just handwritten copies made by him (Hatsumi sensei). Only photos of the originals used for some books written by Hatsumi sensei. Takamatsu sensei was a genius, possessing incredibly deep knowledge and vast wisdom. It made me realize not only my own intellectual limitations, but also how much I still lacked in practice and study. I measured how incredible the task was for Hatsumi sensei, who continued to practice and study without saying anything, showing endurance and perseverance in the patience that Takamatsu sensei presented as the ultimate art of ninjutsu. You can't help but feel small and humble, and that feels good," he said with his amazing smile.

It was during Covid, in January 2021, at Hatsumi sensei's insistence, that Ishizuka sensei began writing his book. I received a call from sensei in Japan that January during Covid: "Hatsumi sensei asked me to write a book telling the story of how we met, with technical explanations and more. I want my words to be translated as faithfully as possible, and you’re the only person who knows me well enough to do it.” So Ishizuka sensei began writing the book of his life, surrounded by transmission documents written by Takamatsu sensei and punctuated by visits to Hatsumi sensei.

In December 2022, with Japan reopened since that October, I was able to visit Ishizuka sensei and Hatsumi sensei. In February 2023, Ishizuka sensei gave me his manuscript and I began the translation work. In early April 2023, I returned to Japan with two professional photographers, to make a video and take photos of Ishizuka sensei for his book, William Ustav and Roberto Chavez. In France, Mohamed Moustaine handled all logistics for the book's printing.

For some reason I don't know, Ishizuka sensei was eager to see his book published, between calm and urgency. During 2023 and 2024, I made several trips to Japan, reassuring Ishizuka sensei about his book, doing my duty as a disciple and writing the book, being present at all stages of writing, translation, commentary, photo selection, etc. And in late March 2024, thanks to the tremendous work of Mohamed Moustaine for logistics and as publishing director, the help of Adrien Ito for the translation, William Ustav and Roberto Chavez for layout and photos, his book was finally published, with a crowdfunding campaign allowing the sale of 800 books in the first week of sales. Sales reached 1,000.

In early April 2024, I visited Ishizuka sensei to bring him his book. I found him very thin, pale, and tired. His condition was alarming, and when I pointed it out, he replied, "It's nothing, just an allergy to pollen." Which I found hard to believe. At the end of April, with his wife, we took him to the hospital, he asked me to take care of the dōjō and classes in his absence. The next day, his wife asked me to go with her to the hospital to see sensei. I still see him alone, dressed in his white kimono, in his intensive care room... and the diagnosis: tracheal cancer, a malignant tumor the size of a fist. According to the doctor, less than a year to live...

From 2024 to 2025, until his funeral, I went to Japan more than seven times, staying by his side...

Photo Tribute to Ishizuka Sensei